There are daughters-in-law who suffer through their own particular brand of neglect - sometimes resented, often ignored. They are prisoners to the incessant demands placed on their husbands by the business to which they are committed: a business these young women do not understand and are not being helped to understand.

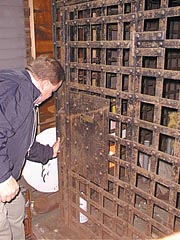

In both cases, these women become unwilling participants to an all-consuming dream they don't (or aren't allowed to) share or understand. They're not prisoners by intent. Nobody wanted to put them into their position. They are prisoners of circumstance.

Maybe the founder didn't want to burden his wife with his business concerns, so he inadvertently cut her out of participating in his dream and sharing a significant part of his life. When she becomes his widow, as is statistically likely, she may find herself totally dependent on a business that is strange to her and on advisors selected by her husband whom she never really got to know. When her future was in the hands of her husband, at least she knew and loved who was controlling her destiny. But with him gone, she may not know who is pulling the strings of her future, or why what's being done is being done. She is the prisoner of an insensitive estate plan, drawn by experts and signed into fact by a man who loved her. She has no guarantee to believe that her future will be the future she wants.

The daughter-in-law can be a prisoner of a set of conflicting loyalties. She is loyal to her husband and what she sees as his requirements. She is loyal to their marriage and their children. He is loyal to her, too, but he also has his commitment to the family business, to his father and to the rest of his family. His wife will support and defend only what she can understand, and if she can't understand the reason for the excessive demands placed on her husband, she won't support him in filling those demands for very long. If she doesn't understand where the business is going and what it will mean to her husband and family, she will not be able to share his dedication. She remains his wife because she loves him, but she feels hemmed in on all sides by the demands of a business she resents. She is a prisoner.

Finally, there are the heirs to the founder who were forced to join the business under pressure - overt or otherwise - from their father and the family. It was expected. Or they were needed. Maybe the family business was the only option they knew because it was the only option they were allowed to see. These heirs can become prisoners, too, because the family-owned business usually is a terminal occupation.

A Terminal Occupation

It's terminal for two important reasons. First of all, the experience gained in a family-owned business usually is not transferable. Working for Dad usually is not a stepping-stone to something else. Instead, it's a specialization, a narrowing of general business interest to a concentration upon one very important, but very unique business problem. It is an experience in which to apply general knowledge and many skills, not just one, which makes the heir more qualified for more common and standardized management occupations. This scenario makes it less and less likely, as time goes on, that the heir will be able to find equivalent work outside the family company. This increasing unemployability, coupled with the common practice of overpaying family members, helps to slam the gate shut on the working heir.The second important reason why employment of family members in the family business tends to be terminal is loyalty. In most any job, the people around the employee depend on him to do the best he can, but in the family-owned business, these people are brothers, sisters, parents or cousins. Their relationships go far beyond business concerns and office Christmas parties. To let them down (by quitting, for example) often means a disruption of one's entire life. Many times, the heir's seemingly only viable option is to hang around, trapped in an unfortunate situation out of love or respect for the founder and/or other members of the family.

For a whole range of potent reasons, many family businesses harbor a number of unwitting and unwilling inmates. They all are prisoners. They all are in a position where they could be enjoying the opportunities and challenges, the freedom and control a family-owned business offers. But there is no enjoyment. They do what they do under duress. They feel put upon and mistreated. They deserve something better.

Releasing the Prisoners

Just as there's no place in a closely held company for incompetence, there's no room for the unwilling, the uncommitted or the bitter. These attitudes are like a slow poison, which builds up in the system until the dose becomes overwhelming. Every business owner presides over one of these potential prisons, but often because of his isolated position as the boss, he's not aware of it.More accurately, it's the founder who both creates the prisoners and remains blissfully unaware that they exist. The successor, on the other hand, very soon becomes quite aware that he is serving as a part-time warden over the people incarcerated during the founder's reign. It falls on him as another one of his urgent jobs to find those prisoners and do everything he can to release them. Finding them isn't too hard; they make themselves known one way or another. It's releasing them that's the problem. Often they're like horses in burning barns, unwilling to leave. Even more often, they just aren't ready to make it in the outside world.

The long-term, less-than-adequate managers have devoted their entire working lives - or at least a great portion - to the company. For them, it's an essentially terminal occupation that becomes more terminal as time goes by. Usually they have been brought to their precarious positions by a series of misdirected management and personnel decisions. Competent or not, there's a tendency for employees in a family-owned business to become helpless and immobile - often because they have been sidetracked by the founder or frustrated in their ambitions.

Entrepreneurial bosses have a tendency to inhibit their people, often refusing to let them work on their own and condemning them to second-class managerial positions. These employees can either become too scared to get up and get another job, or they feel they've been in the same job so long that their experience is out-of-date and irrelevant.

Often, They're Right

The hard fact is that a middle management job in a family company can turn out to be a real dead end for an ambitious person. An employee of a family-owned business who's done little else just doesn't have the world's greatest chance to become a responsible manager for another company. That shift is more likely to occur during their 20s and 30s. After that, they tend to become prisoners of their job. They're stuck.The successor is, therefore, often stuck, too. If he looks over his payroll, he'll often find that the older employees tend to group at extremes of the pay scale. They are not very competent and the company keeps them at low pay, while they haunt the place like ghosts - or, because of years of loyalty and ill-considered automatic raises, they are so highly paid that nobody in his right mind would hire them at their present salary. They didn't come to be where they are by themselves. They had help from the company they've devoted their careers to.

Report Abusive Comment