What is a jet pump and how does it differ from a centrifugal pump?

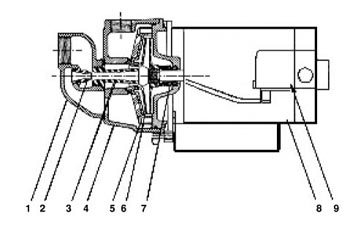

A jet pump actually is two pumps in one: a centrifugal pump and a jet assembly, commonly called an injector. Figure 1 shows a typical shallow well jet pump. Parts 1, 2, and 3, the adapter, nozzle and venturi on the left side of the pump are the injector or jet components. We refer to the entire package – the centrifugal pump and injector – as the jet pump. The centrifugal pump part of a jet pump package is specifically designed to operate in conjunction with an injector, and the injector enhances a centrifugal pumps pressure capability by about 50 percent.Shallow well jets have the injector attached to the pump above ground level and are limited to about 25 feet of lift, just like straight centrifugal pumps. Their only advantage over a straight centrifugal is their pressure boosting capability.

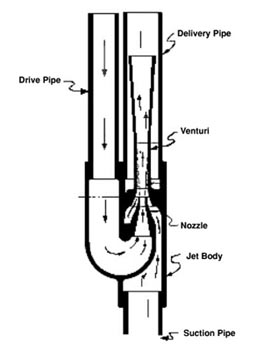

Deep well jets, on the other hand, have their jet injector down in the well below the water level, so they push the water to the surface. See Figure 2. Deep well jet pumps are not limited by atmospheric pressure to 25 feet of lift. A good deep well jet can pump water from as deep as 200 feet. Remember, when we say we are pumping from 200 feet, we are referring to the distance from the surface of the water in the well to the discharge point at or above ground level, not from the injector to the discharge point.

If the jet pump is so designed that the injector can be either attached directly to the pump or located down in the well, it is known as a convertible jet pump. Convertible jet pumps therefore can be operated as either a shallow well jet or a deep well jet. With that background, we now will look at the jet assembly to see how it functions.

This diverted portion that powers the injector, called drive water, is directed through the nozzle where it accelerates just like water passing through the nozzle at the end of a garden hose. The drive water stream is directed through a gap toward the venturi, creating a partial vacuum at the gap. Here, atmospheric pressure forces product water (well water) to enter the injector and mix with drive water as it enters the venturi. The outward flair of the venturi reduces the velocity of the stream as it passes through, converting it back into pressure and directing it into the eye of the impeller where it is further pressurized. Upon leaving the impeller, a portion exits the pump to become service water, and the rest is returned to the injector as drive water.

Deep well systems are broken down into two sub-types, double-pipe and single-pipe. When the well casing is four inches or larger in diameter, a double-pipe system normally is preferred. Where the well casing is smaller than four inches in diameter, a single-pipe deep well injector can be used. It differs from a standard two-pipe deep well injector in that it is smaller in diameter, is hung from a single suction pipe and includes packers that seal against the casing. A well casing adapter seals the top of the casing and provides a means of introducing feed water into the casing. With both ends sealed, the well casing acts as the second pipe for the drive water. Obviously, for a single pipe injector to work properly, the casing must be in good shape.

To keep jet pumps primed, it is important to install a foot valve at the bottom of the suction pipe to prevent the water in the system from draining back into the well when the pump is off. This applies to all types of jet pumps.

A question that often comes up: Will a jet pump work without the jet? The answer is yes, but… Yes, because it will pump water, but no, because it may destroy itself by pumping too much water. One of the advantages of a jet pump is that it cannot be overloaded on the horsepower curve because we create artificial head with the pressure regulator and nozzle. Without the jet assembly, a jet pump can pump beyond its curve, draw too much power, overheat the motor and possibly burn it up. Bottom line: Don’t use a jet pump without the injector.

We will continue this discussion of jet pumps in next month’s issue with a close look at jet pump control valves. ’Til then,....

Report Abusive Comment