Environmental drilling first took hold in the early 1990s. More than a decade later three companies that work in the environmental field provide different services, use different techniques and give different opinions on where the environmental drilling industry is going.

Sunbelt Environmental Services Is New to the Field

Only since about 1998 has Sunbelt Environmental Services Inc. in Springfield, Mo., been involved with environmental drilling. Sunbelt originated in 1986 as a one-person waste brokerage known as Sunbelt Industrial Services that provided services from Texas up to Chicago. In 1993, Tom Underwood and Lee Schaefer bought out the Springfield branch and changed the name to Sunbelt Environmental Services Inc.The company got started in environmental drilling because "we were spending a lot of money subcontracting out that work," says Sunbelt geologist Donny Nowack. "It came to the point that we were hiring other firms so much to do our drilling that we thought we would go ahead and get a rig."

The company lucked out by having a client who owned its own rig for a big project and was done using it. The client wanted to put the rig out for sale, so Sunbelt just bought it and got started drilling.

The company now owns a Mobile B 53 and a geoprobe. While Sunbelt employs about 28 people, only five people, including Nowack, focus on environmental drilling.

"We got started pretty much from scratch," he remembers, "so it's evolved a lot since the beginning. We found out a lot of the techniques that we do now for the shallow rotary drilling and learned from a lot of mistakes.

"We ended up hiring a water well driller and having him help us get started with the air rotary work, and then we had another guy on staff already that had done a lot of drilling in the past. We started with these guys and started going out doing jobs and learning. But, we had some experienced staff."

Geoprobing

Most of Sunbelt's business comes from soil and ground water sampling and the installation of ground water monitoring systems, Nowack says. The company also offers hazardous and non-hazardous waste disposal, assessment and investigative services of Phase I and Phase II, UST removal and remediation, lead paint, asbestos and mold remediation, air and storm water permits and geologic work.Sunbelt's clients are mainly in the industry or they are other environmental companies that subcontract all their drilling work.

"For us in our area, we've really got the market cornered in shallow air rotary drilling," Nowack says. "Most of the environmental drilling firms around here only do auger drilling in the soil, and we've got it set up where we can do shallow bed rock drilling up to about 100 feet for a real reasonable price. That seems to be where most of our business from other companies has come from. When it comes to auger drilling, most of our competitors get that work."

Nowack says the company doesn't look like it will be going in the direction of auger drilling.

"We see ourselves moving more toward doing the geoprobe work," he says. "That really has been our success."

Nowack also doesn't see any equipment changes coming in the near future.

"I think we're probably mostly going to expand into the geoprobe work," he says. "I don't know if we'll ever add on or get another drill rig. I think geoprobing is where the future of a lot of environmental drilling is going to be. It's getting to where the EPA and most of the state equivalents will be allowing these geoprobe wells to go in, instead of your traditional auger drilled wells. You can put in a 1-inch diameter well with a geoprobe at a significant reduction of cost and it will perform just about the same."

Duane Moyer Well Drilling

Duane Moyer Well Drilling Inc.'s (Lehighton, Pa.) environmental drilling business began with local firms coming to them."We basically were hired by firms to do local environmental work in our area, and then we just grew from that," says vice president of the company Scott Moyer. "We realized that we enjoyed that field of work and we grew that into the business from there."

Duane Moyer Well Drilling Inc. was established in 1969 by Scott Moyer's father and mother. The company provides well drilling, water conditioning and water system services to more than 10,000 homeowners and builders throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and West Virginia just to name a few locations. All this drilling is done with the help of 15 employees and two Ingersoll-Rand T-4s.

"No specific number of employees work strictly with the environmental drilling aspect of the company," Moyer says. "All our drillers work in every aspect of the company. We do residential, commercial and geothermal also."

The company provides environmental services such as drilling monitoring wells, vapor extraction wells and recovery wells. The environmental drilling services that Moyer Well Drilling provides include soil and split spoon sampling, monitoring well design, construction and installation, aquifer testing, well abandonment and pressure grouting.

"Most of our environmental work is bedrock monitoring wells," Moyer says. "Ground water monitoring wells make up 90 percent of our work."

Normally, engineering firms and consultants make up most of their environmental drilling clientele.

Moyer sees the field getting more professional, especially in the ways of the installation of wells and construction of the wells itself. He also sees new technology in sampling equipment - "not that our company uses it," Moyer says.

"Actually, we are looking into a third machine dedicated to the environmental side of the business," he says. "More business has been coming from the environmental drilling?here is always going to be a need for monitoring wells around gas stations, which is a large percentage of this industry."

Hansen Environmental Drilling

Steve Hansen, vice president and driller for Hansen Environmental Drilling Inc. in Glasgow, Mont., went to Montana Tech and became a mining engineer. He worked at a gold mine in southern California in the late 1980s where he was in charge of the monitoring wells. Hansen wanted to move back to where he grew up in Montana and his boss told him what a big business environmental drilling was going to be."So, on what he said and my history in the past - my brother has a drilling company and I've helped him some and I've ran an auger rig some - I just jumped in in '91 thinking that this was going to come, and then learned as we went," Hansen says.

The company began in 1991 with auger drilling and monitoring wells. Around the same time, tank regulations came into affect with underground storage tanks and the government wanted work done on a lot of military bases across the United States, so Hansen began doing these jobs.

"There weren't a lot of people doing it, so we were able to fill that niche in the early- and mid-90s," Hansen recalls.

Now the company does geotechnical drilling with augers, quarrying, mud rotary drilling and some water well drilling too in eastern Montana, Wyoming and occasionally in North and South Dakota.

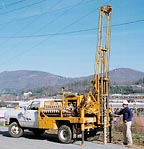

Hansen drills on a 1998-CME high torque auger drill that is truck-mounted with the assistance of a helper. "CME makes really good equipment that has a lot of safety features," he says. In environmental drilling, most of the company's work is done with hollow stem augers like a 2- or 4-inch monitor well.

"You're able to keep better track of what's going on when you're an owner/operator running the drill," Hansen believes. "You know what's going on with your equipment and your clients. The business has grown each year."

The company currently does a lot of underground storage tank work where Hansen is drilling at gas stations and at underground tanks. The company also works at oil refineries and does site assessments at dry cleaners and other commercial properties or at real estate transactions.

Hansen Environmental Drilling only does the drilling. The company subcontracts with engineering firms.

"We don't compete against other engineering firms, because we don't do any of the engineering or anything like that," Hansen says.

Hansen explained that engineering companies that do both the engineering and the drilling get into a conflict of interest when the engineering part of the business is competing with other engineering companies. Another engineering firm might get the work and hire your engineering firm to do the drilling. It's a stickier situation, he says.

"We don't have that," Hansen says. "We're strictly a sub to engineering companies."

Future Trends

Hansen sees future business in environmental drilling going to companies that have solid safety records."Although price is important and many times companies want a really low bid, safety and safety records and your health and safety program are becoming more and more important," he says. "Especially when you're working with bigger companies.

"We have a good safety record and always wear all our safety equipment. I could site specific examples about some firms that don't wear their hard hats and have some really bad accidents with helpers. If they are drilling for a big oil company, that company and the engineering firm are only opening themselves up for a lot of liability. You see more and more companies hire you if you have a good safety record, more than on just price."

Hansen says the industry also is seeing fewer companies using junky equipment and running really cheaply.

"The engineering firms just don't want to be standing around with the machine broken down," Hansen says. "We've always ran new equipment, but you have to charge more money because of it. To have good people and good equipment, you have to charge a fair price so you can make your payments to your people and on your equipment."

Hansen says the industry has more geoprobes coming out to do work, which are often, in his opinion, under powered or can't go deep enough.

"The engineering firm tries to go cheaper the first time with a geoprobe, but then they can't get down through the gravel and clays," Hansen says. "So, then they have to call in an auger rig and help them retrieve their tools and complete the job.

"When they make a geoprobe hole, they make a really small hole, like a 1-inch or 2-inch hole, and it's really hard for them to ever seal that. Say you push a 1-inch down through some gasoline or diesel or other contaminants. A geoprobe [user] will tell you that you can seal that up, but it's really hard sealing a 1-inch hole versus if you have a 8-inch hole for grouting or cementing it from the bottom up. I really question whether those holes are ever grouted or sealed properly and can be, although they will tell you they can.

"The main reason why people ever get a geoprobe is because they think they can make more money with it by doing it a little cheaper. Everything is price sensitive. But if they get out there and can't complete the job because of the gravel, it looks bad for the engineering firm and everybody involved.

Hansen cautions readers that "We don't have direct push or geoprobe stuff, so we're probably pretty bias against it."

Being at a subcontracting company himself, Hansen believes that a promising future exists in the environmental drilling industry for a company like his. According to Hansen, firms that run new equipment, have a really good safety record and are user friendly and don't compete with engineering companies will find that engineering firms want to hire them because they don't compete with them on the engineering.

"Most engineering companies are just interested in the engineering and the report writing because that's where the money is," Hansen says. "They don't want to be feeding their competitors by hiring one of their engineering competitors that has a drill rig because then they are really over a barrel about what they are going to charge. Or an engineering firm could hire another engineering firm that has a drill rig and then that engineering firm could steal the job from them. I could cite a hundred examples of that. That's where the conflict of interest comes. If one of your competitors steals a project because you called them up to get a price on the drilling, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth. And it happens a lot."

Report Abusive Comment