“Clean water, well pumps that work and ways to treat the water to avoid diseases become very important to you because you realize that people really need these things,” says MIT graduate student Luca Morganti of Milan, Italy. “You appreciate the fact that what for us is maybe just an unusual assignment, is everyday life and work for the local people.”

In Nepal, one out of 10 children under age five – around 44,000 – die every year from waterborne diseases, according to Susan Murcott, a lecturer in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. She led the graduate students to Nepal where they visited Kathmandu; the birthplace of the Buddha, Lumbini; and small villages nearby.

At the most basic level, Murcott says, there are two treatment processes necessary to provide clean drinking water at the village well: removal of particles and inactivation and/or removal of the microorganisms that cause disease. The microorganisms attach to particles, so removing the particles “also removes about 90 percent of microbes. Then you have to get rid of the rest of the microbes,” she explains.

The team has been identifying and testing a variety of potential systems that could be appropriate for developing countries with the key criteria being technical performance, “low or no” cost (the average annual income in Nepal is $210), social acceptability and project sustainability. Morganti, who will return to Nepal to continue the work after he receives his masters degree in civil and environmental engineering, says, “You find that what you are experimenting on for the first time has been studied by the local people for a long time, and they have valuable experience to transfer.”

Children Join In

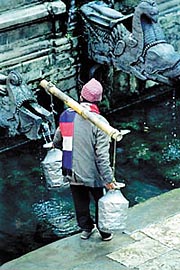

"The villagers couldn’t help enough,” says Donna Coveney, the MIT News Office photojournalist who accompanied the Nepal team. “Everyone wanted to lend a hand.” At one stop, she recalls, two children grabbed the hands of Jeff Hwang of Topeka, Kan. “They went off with him to help pump a water sample from the well across the street. I think the little girl who pumped put her whole heart and soul into it, just for Jeff.” Another graduate student, Jason Low of Singapore worked with a Nepalese potter, Hari Gobindh, to create ceramic filters for removal of particles. “It was very exciting to watch them working together to mitigate the problem,” says Coveney. “Two good hearts and two good heads working together to help the Nepalese people.”

The water project taught students much more than the mechanics of pumps and filters. “I’ve seen on TV the lives of poor people in developing countries, but that was nothing compared to seeing [poverty] before my own eyes,” said Tommy Ngai, of Scarborough, Ontario. In the rural villages he visited, “most people did not have modern comforts such as running water or a reliable power supply.” Ngai did most of the cooking for the Nepal team on a tiny propane stove that doubled as a water heater for various experiments.

Chlorine Generator

The team evaluated a pilot chlorination project set up by other team members a year earlier. Chlorine is the principal disinfectant worldwide, but it was largely unavailable in Nepal. The team discovered, however, that the chemical could be imported from India. “We also were told that villagers wouldn’t use it because they thought the water wouldn’t taste right,” Murcott explains. To test that assumption, the pilot program provided enough chlorine, buckets and spigots to supply 50 households and four schools for a year. “And it was a success,” Murcott beams. “People used the chlorine, and sickness went down.”

Report Abusive Comment