The main piece of equipment on a typical drill site these days, quite commonly, is powered by a diesel-fueled engine. Still, it still remains likely that there’s a whole range of gasoline-powered products in use, ranging from those small handheld products through the newest and biggest air-cooled behemoths.

We’ll look today at the current state of things when it comes to gasoline as a fuel source. We’ll consider things from an engine availability standpoint, as well as from the standpoint of effective and uninterrupted operation for any and everything powered by this precious fuel.

Not surprisingly, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emissions regulations have a firm hand in all of this.

The Handheld Stuff Did Not Disappear

What could be more powerful and effective for someone expecting to get some serious mobile work done than a lightweight tool with its own integrated power source? Let me suggest, not much. And such tools continue to go to work for us every day, despite earnest efforts in establishing serious (low) emissions values for the initially all two-stroke engines used in these products. Think of such things as chainsaws and earth augers and blowers finding spots with work crews all over the place.

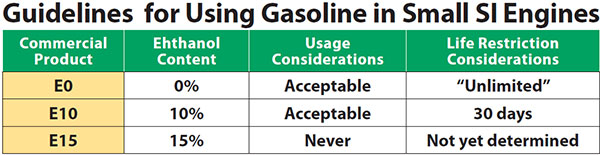

Their needs remain simple. They like fresh fuel, less than 30 days old if it’s standard E10 — that is, containing 10-percent ethanol. Or, even better, a source of E0 (no ethanol whatsoever, and mostly available in rural areas) so that concerns about ethanol-related damage will be nonexistent. Be sure to mix the required oil, of course. It’s the wise operator who works out a means to minimize potential for engine failure because straight gas was used when it shouldn’t have been. Proper labeling. Dedicated containers. These sorts of things.

For those interested in and able to use a particular product or two powered by one of the mini 4-strokes that have been developed (no oil mixing necessary, thank you very much), the size of these continue to increase with the recent introduction of one at 50 cc and a full 2.0 horsepower. These represent a significant increase in size, power and capability in the world of handheld engines. Worlds of opportunity will open as OEMs start integrating them.

A Bunch of the Utility Stuff is Always Near

What could be more pleasant sounding than a product powered by a small utility engine calmly running hour after hour on a busy worksite? Let me suggest, once again, not much to those who truly relish the opportunities to get serious work done. Perhaps it’s simply running a small pump, generator or specialized tool. The importance of these small utility engines only increases with time.

While also subject to EPA emissions regulations, they run cleaner than ever and continue to get technical updates that make them more durable and easier to operate. Enhancements include such things as EFI (electronic fuel injection), which improves overall performance and response, and minimizes potential ethanol damage as compared to a carbureted engine with a float bowl. Another enhancement, directly related to that, is the recent addition of an electronic throttle body on some select larger engines — a means to directly control the intake air to ensure the very best mixture and throttle response.

Individual improvements include more effective intake air cleaning strategies. For example, directing more of the unwanted dust away from the air cleaner. If dust never even reaches the air cleaner, it won’t start plugging up. Then, using air filter elements of greater surface area and, thereby, capacity.

The basic needs of these little wonders are simple as well. The aforementioned fresh fuel requirements apply here also. But from a lubricating oil standpoint, it’s best to pay a little special attention. As the world of automotive oils becomes more complicated, it isn’t quite as simple to simply select the most current one from this group and use it in the small engines. A number of engine companies now offer their own oil and there are several reasons that picking and sticking with one of these would be beneficial and recommended.

We know that it’s 100-percent approved for usage. Pretty clear that the oil was not the problem if a warranty situation arises. It’s also pretty clear from the container what product the lubricant is to be used with. That minimizes chances of mis-oiling. But, recent news is that blenders are adding such things as more zinc, which is sometimes minimized in automotive blends as it tends to damage catalytic convertors. Little engines, however, adore this sort of extra protection — provided just for them.

So What’s This “Big Block,” and When Did It Appear?

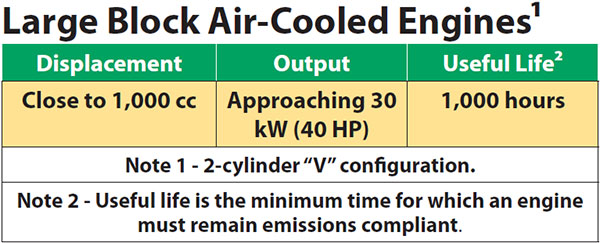

An interesting “carve-out” in the Small SI Emissions Regulations revolves around the 1,000 cc displacement level and the initial 25-horsepower output level it was matched with.

In developing the Small SI Regulations, the EPA set an upper level of 1,000 cc for these air-cooled engines, which at the time were producing at best around 25 horsepower (19 kW). The key point is that the testing of these, as well as the requisite useful-life (the time over which an engine needs to be emissions compliant, in effect a determination of its durability), was set at 1,000 hours. Compare this to automotive-based, liquid-cooled SI engines (not to be covered specifically here) that require a durability of 5,000 hours, with the necessary testing burden.

EPA subsequently raised the upper horsepower limit to around 40 (30 kW) and here is where things are now interesting. It is possible to produce an engine generating up to that 40-horsepower level that is nowhere near as complicated as an automotive type with its liquid cooling and full electronics, and that challenging 5,000-hour durability requirement. Of course, these engines were quickly developed by the air-cooled engine folks and are finding their way into many more products.

One would be savvy to search out such a power package if available. Some real power. And lower costs in purchasing. And good fuel economy overall, as the days of excessive fuel running through engines to act as a secondary cooling effect are long behind us. Most of the fuel going in will be fully combusted.

For Gasoline, This is Now “The Year”

In the news recently have been the announcements by the EPA regarding the imminent arrival of E15 (15-percent ethanol) gasoline blend on a year-round basis. Making it possible to sell this product at all times supports fuel stations’ interests in investing in requisite dedicated pumps to serve it up.

The small-engine folks are concerned, as this stuff is not suitable for small-engine products, including outboard marine engines and a whole range of other products. Things at the fuel island are confusing enough already, with all the warning signs and offers of treats inside the store distracting consumers. The possibilities for mis-fueling are very high. The fact that an E15 product might be the lowest-priced offering only increases the chances.

Industry surveys have confirmed the limited knowledge of the average consumer regarding gasoline fuels. And what might, therefore, unfortunately start happening with some regularity? Actual and unnecessary engine damage. The ethanol folks driving this change are not to be deterred — interested primarily in increased sales of ethanol.

But we, as professionals at this sort of stuff, need to be sure that anyone and everyone who might get anywhere near a red container understands all of this fully so that one does not inadvertently become an unwelcome statistic from using E15. And the sooner this is fully explained, the better for all.

Regarding all of this, I do hope I’ve been perfectly clear.

Report Abusive Comment